In both cases, the low rate is established through a deduction that corporations can claim once their taxable income is tallied.

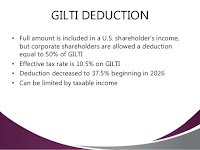

While the TCJA exempts most worldwide income from taxation, under GILTI it immediately sweeps in some foreign earnings, defined as intangible through a formula based on the amount of tangible assets the company holds offshore, and taxes them as if they were U.S. income. Corporations can then apply the Section 250 deduction and receive the low 10.5 percent rate. But that second step did not seem to be available to individuals, even though their income would still be taxed under GILTI.

That disparity left individual taxpayers with the possibility of a 37 percent rate on their overseas intangible income, what many considered to be an unfair and onerous burden.

Tax practitioners immediately explored the possibility of electing for corporate treatment under Section 962. But 962’s history indicated that it ensured only that individuals paid the same rate as corporations, not that they had access to the same deductions as corporations.

Citing a section of Section 962’s legislative history, stating that its purpose was to ensure that individuals’ tax burdens would “be no heavier than they would have been had they invested in an American corporation doing business abroad,” the proposed regulations mandate that income under Section 962 would be reduced by the amount of a Section 250 deduction that would have been available to a domestic corporation.

The proposed regulations are also the first window taxpayers have had into what kind of documentation Treasury will use to determine if a company is eligible for an FDII deduction.

FDII mirrors the treatment of GILTI, providing a 37.5 percent deduction on intangible income held domestically and equaling a rate of 13.125 percent. The provision is similar to a patent box, a popular policy in Europe that grants a lower rate to intangible assets such as intellectual property held in the jurisdiction. But the FDII deduction is available only on foreign sales.

Treasury outlined a series of rules and tests that companies would have to satisfy to verify that their income was really from foreign sales. Those rules also include exemptions to some of the documentation requirements for small businesses, or those with less than $10 million in annual sales or less than $5,000 from an individual customer, which were not set in the legal language of TCJA.

In the regulations Treasury also indicated it would distinguish between sales and services, which receive different treatment in the statute, based on the “overall predominant character of the transaction.”

Government officials in Europe and elsewhere have criticized the FDII tax benefit, claiming it subsidizes exports and ignores requirements from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development to include requirements that benefits to intellectual property be paired with real research and development. Challenges before both the OECD’s Forum on Harmful Tax Practices and the World Trade Organization are expected.

Read more at: Tax Times blog