Ask the federal district court of California, which recently upheld the IRS’ imposition of separate non-willful penalties against 13 foreign accounts disclosed on a single late FBAR return. The court’s decision raises the stakes for taxpayers looking to quietly report their foreign interests to the IRS and debunks the common notion that the non-willful FBAR penalty applies on a per-year basis.

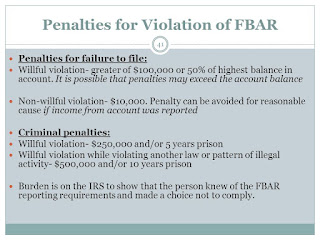

A nonwillful failure to comply with the FBAR reporting requirements can result in civil monetary penalties if (1) the breach was not due to a reasonable cause, and (2) the account balance was not properly reported.(31 U.S.C. §§ 5321(a)(5)(A) and (B)). As a result of such violations, the Internal Revenue Service is authorized to impose a maximum penalty of $10,000 on any person who fails to comply with the BSA. The penalty may be imposed separately on each joint holder of a foreign financial account (31 U.S.C. §§5321(a)(5)(A).

The statutory language of the BSA does not clarify whether the $10,000 maximum penalty is applicable per calendar year or per foreign financial account. The IRS had historically taken the position that the limitation could be imposed on each of a taxpayer’s unreported accounts and therefore, the limitation did not constitute an annual cap (IRM 4.26.16.6.4.1 (11-06-2015)). This approach was widely criticized by practitioners and in May 2015, the IRS responded by issuing interim guidance indicating that it would instead impose the nonwillful FBAR penalty limitation on an annual basis in certain circumstances going forward (SBSE-04-0515-0025 (May 13, 2015)).This guidance explicitly retained the IRS’ flexibility to apply the FBAR penalty on a per financial account basis where warranted.

In United States vs. Jane Boyd, the taxpayer had a financial interest in and/or otherwise controlled 14 financial accounts in the United Kingdom with balances collectively exceeding $10,000. Boyd was required by law to file a Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (“FBAR”) form disclosing her interests in her U.K. bank accounts for 2010, but failed to timely do so.

Boyd participated in the IRS’ Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program in 2012, but later opted out in 2014. The opt-out gave rise to an IRS examination and an initial taxpayer-favorable determination by the IRS that Boyd was not willful in failing to timely file the FBAR for 2010.

Not so favorably, however, the IRS assessed 13 separate FBAR penalties against Boyd, treating each reported account as a separate non-willful violation. One account was not penalized based on IRS mitigation rules.

After Boyd refused to pay the penalties, the Government filed suit in federal district court. Both parties later filed competing motions for summary judgment.

The Government argued that the statutory maximum penalty of $10,000 under 31 U.S.C. § 5321(a)(5)(B) for non-willful violations related to each foreign financial account, whereas Boyd argued that, if there is a non-willful failure to file an FBAR, the penalty cannot exceed $10,000 regardless of the number of bank accounts required to have been listed on the FBAR.

The court explained that the BSA is ambiguous with respect to the applicability of the $10,000 maximum penalty but agreed with the IRS that it is more appropriately interpreted to impose the penalty on each unreported foreign financial account rather than per calendar year.

The court found support for this decision in the language of the reasonable cause exception for nonwillful FBAR violations. Specifically, the court cited that a penalty would not be imposed if there was reasonable cause for the violation and “the amount of the transaction or balance in the account at the time of the transaction was properly reported.” The court was persuaded by the IRS’ contention that by making reference to a singular account, Congress intended for taxpayers to be penalized for each foreign financial account violation rather than for a collective calendar year. On that basis, the court decided in favor of the IRS. This decision may be appealed by the taxpayer.

The implications of the Boyd decision are far reaching. Even unintentional taxpayers now face exposure to material FBAR penalties of up to $10,000 per account per year. With the IRS benefiting from a 6-year statute of limitations period for FBAR penalties, a taxpayer with four accounts could be facing non-willful penalties upwards of $240,000. Another example is where an unintentional failure to report three foreign financial accounts that were jointly held by two taxpayers over a three-year period could result in a total maximum monetary penalty of $180,000, as opposed to a maximum penalty of $60,000 that would otherwise be imposed under the calendar year approach.

This more-expansive penalty exposure changes the risk/reward ratio for taxpayers considering an opt-out of the IRS’ voluntary disclosure program, as well as those taxpayers assessing whether to quietly disclosure their foreign interests or otherwise apply for the IRS’ streamlined filing procedures and pay only a single 5% penalty.

Given the broad scope of direct and indirect financial interests and authorizations that implicate the BSA, as well as the numerous types of relevant foreign financial accounts, United States individuals and entities should perform annual reviews of legal and beneficial asset portfolios, bank account authorizations, executive and board of director duties, trustee and executor relationships, and any other potential positions of effective economic control.

The Boyd case suggests that the IRS could be transitioning to a more aggressive penalty approach for FBAR violations and United States taxpayers should take proactive steps to protect themselves from the increased risk.

Sources

Read more at: Tax Times blog